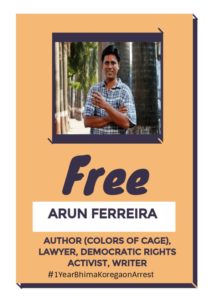

Who is Arun Ferreira?

Arun Ferreira is a human rights lawyer from Mumbai, India. He is a member of the Committee for Protection of Democratic Rights (CPDR) and the Indian Association of People’s Lawyers (IAPL). He studied at Mumbai’s St. Xavier’s College where he developed a strong social conscience, and organised the institution’s canteen workers to demand better work conditions. After college, he worked with slum dwellers in Mumbai before becoming a community organiser in Vidarbha (rural Maharashtra state).

Ferreira was arrested in 2007 in a much publicized case where he was accused of being a ‘Naxalite’ – a term that has come to be used interchangeably with the term ‘Maoist’ in India, a political movement/group that was banned in 2004. One of the accusations against him was that he was plotting to blow up Deekshabhoomi in Nagpur, where Dr. B.R.Ambedkar – chief architect of Indian Constitution – converted to Buddhism. Over the course of four years, he had ten cases slapped against him under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), which is applied to those that the state believes might commit crimes against the state. None of the charges against Ferriera were proven in court and he was acquitted of all charges in 2014. He was released from prison after spending four harrowing years, undergoing brutal torture and subjected to narco-analysis (which is illegal under Indian and international law).

In September 2011, Ferreira was finally granted bail, but what followed was doubly traumatic. In a replay of his 2007 arrest, he was immediately taken to a police station in Gadchiroli district. The arrest was made for two cases of ‘Naxalite’ attacks in 2007 and the court allowed police custody even as Ferreira complained of abduction. The case against him was registered three days before the police recorded statements by witnesses, a violation of basic criminal court procedures.

This re-arrest turned the tide. The media coverage was more sympathetic this time. Protests took place and a petition was filed for his release. On January 4, 2012, Ferreira stepped out of prison and made it home. He later wrote an acclaimed book about his prison experiences which has been translated into several languages. He recounts the events of that day in his book’s last chapter, which begins with the sketch of a man breaking free, the word azaadi (freedom) inscribed in the background. In truth, it would be another two years, until his acquittal in the last of his cases before Ferreira could truly “feel free”.

Drawing by Arun Ferreira

After his release, Ferreira studied to become a lawyer and became part of a large group of legal professionals working for the release of the five activists arrested in June 2018 in the Bhima-Koregaon case.

This in turn led to his subsequent arrest, again on the same set of trumped up charges. On 28 August 2018, Indian police simultaneously arrested five human rights defenders (among them Arun Ferreira) and raided the properties of several others in a nationwide operation. The arrest of the five was said to be based on evidence of their “involvement in inciting violence” on 31 December 2017 during the Bhima-Koregaon event. After a month under house arrest due to a stay order by the High Court, Arun Ferreira along with another of the arrestees (Vernon Gonsalves) were taken into custody on October 26, 2018.

Brief Biography

Ferreira’s career and interests in social activism were strongly influenced by his close relationship with his family, specifically his uncle, Father Raymond D’Silva, who was a liberation theologist. As a member of the All-India Catholic University Students’ Association, he began to explore the strong connections between poverty and lack of social justice. Ferreira attended St. Xavier’s College in Mumbai in early 1990s and as a student, he took a large part in an organization called Cheshire home, assisting in reading to blind children and orphans. After graduating, Ferreira worked with slum-dwellers and squatters of Mumbai, where he became involved in helping slum rehabilitation at Dindoshi and worked for the relocation of slums from Colaba to Goregaon in Mumbai.

In college at St Xavier’s, Mumbai, in the early 1990s, Arun Ferreira was the “khoon cartoonist” (‘blood cartoonist’), a young man with an unusual way of aiding the annual blood donation drive. Whoever donated blood received a keepsake in the form of their caricature, which Ferreira made on the spot. Over time, as Ferreira turned to full-time activism, sketching took a backseat.

His son was two when Ferreira was imprisoned in 2007. As a political undertrial, his time at the Nagpur jail (four years, eight months) was largely one of solitary confinement; books and letters were his reprieve. He again took up cartooning, a skill he had forgotten since he left college.

But soon, in the sweltering heat of Vidarbha, he found himself sketching scenes from prison life. In a monochrome sketch, a jailer welcomes a new convict with a kick. In another, the loneliness of an inmate is apparent in his body language. Ferreira knew the images could become an eye into the world of the castaways. The 30-odd sketches he drew were the beginning of Ferreira’s book Colours of the Cage (Aleph). “One can see what goes on in a police station, but jails are hidden away from the world,” said Ferreira.

Ferreira’s book, and his views

While in jail, Ferreira wrote. His book, Colors of the Cage exposed the brutal conditions of prisons and the existence of large number of political prisoners in India. “A day in the prison begins with sunrise and ends with sunset, where tea is served at 7 am and dinner at 4.30pm, a rule drafted at a time when there was no electricity,” he says. He recounts how prisoners who groan in their sleep are often beaten up; how those convicted of rape get the worst of it, being made to crawl in the afternoon sun by other convicts; and money can get you anything inside, drugs, mobile phones or sexual favours.

Drawing by Arun Ferreira

Some excerpts from his book:

“The anda (‘egg’) barracks are a cluster of windowless cells within the high-security confines of Nagpur Central Jail. To get to most cells from the anda entrance, you have to pass through five heavy iron gates, [and] a maze of narrow corridors and pathways. There are several distinct compounds within the anda, each with a few cells, each cell carefully isolated from the other. There’s little light in the cells and you can’t see any trees. You can’t even see the sky. From the top of the central watch tower, the yard resembles an enormous, airtight concrete egg. But there’s a vital difference. It’s impossible to break it open. Rather, it’s designed to make inmates crack.

The anda is where the most unruly prisoners are confined, as punishment for violating disciplinary rules. The other parts of Nagpur jail aren’t quite so severe. Most prisoners are housed in barracks, with fans and a TV. In the barracks, the day-time hours can be quite relaxed, even comfortable. But in the anda, the only ventilation is provided by the gate of your cell, and even that doesn’t afford much comfort because it opens into a covered corridor, not an open yard.

But more than the brutal, claustrophobic aesthetic of the anda, it’s the absence of human contact that chokes you. If you’re in the anda, you spend 15 hours or more alone in your cell. The only people you see are the guards and occasionally the other inmates in your section. A few weeks in the anda can cause a breakdown. The horrors of the anda are well-known to prisoners in Nagpur jail, and they would rather face the severest of beatings than be banished to the anda.

While most prisoners spend only a few weeks in the anda or in its cousin, the phasi yard, home to prisoners sentenced to death, these sections were where I spent four years, eight months. This was because I was not an ordinary prisoner. I was, as the police claimed, a ‘dreaded Naxalite’, ‘Maoist leader’, descriptions that appeared in newspapers the morning after I was arrested on 8 May 2007.”

Despite being tortured and abused in prison, Ferreira said that his resolve to fight state oppression has only been strengthened. He studied and became a lawyer to help other innocent people who have fallen into the clutches of the law. He also started to research the history of Mumbai’s democratic rights movement and to be associated with the Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners.

“I want to work for the cause of political prisoners because I have realised that any struggle inside jail will die out without support from outside,” Ferreira, 42, told Scroll.in. Throughout his jail term, Ferreira saw his family only twice every three months, and did not meet his young son at all.

His own story — the abduction-like arrest under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) on charges of sedition, the torture in police custody, the false charges which were eventually thrown out by the court in January this year — reveals, he says, the state’s growing intolerance of political activists. At a coffee shop in Mumbai, Ferreira is composed as he talks about his arrest on charges of being an alleged Naxalite in 2007. Other striking cases of the government accusing activists of sedition or arresting them under the UAPA would soon follow — Dr. Binayak Sen in Chhattisgarh (May 2007), Vernon Gonsalves (2007) and members of the Pune-based cultural group Kabir Kala Manch (2011), among others. “Those subscribing to the Naxal ideology are being booked for sedition, even if they aren’t violent. They are being projected as anti-national merely by association,” says Ferreira, citing the example of GN Saibaba, the Delhi professor, who was arrested on suspicion of being a Maoist. Ferreira, who suffered severe physical torture at the hands of the police, believes his case drew attention from the press largely because he stood out as a person from Mumbai. “Many tribals from Gadchiroli and other districts are routinely arrested and abused like this,” he said.

Despite his traumas, Ferreira harbours no anger towards the policemen who tortured him. “The lower officials were just doing their job,” he said. “But what’s worrying is that in the past ten years, the amount of torture of prisoners has increased.” This intense kind of violence, says Ferreira, is reserved for those accused of Naxalism or insurgency, and meted out with the blessings of the state.

Ferreira believes the growing number of arrests and re-arrests under such acts are an attempt by the authorities to artificially inflate their statistics of Naxalites that they have acted against. “As an incentive by the state, all officials get an 11% salary hike for taking action against a high number of Maoists,” he said.

Once arrested, a suspected Naxalite has no option but to wait out the lengthy judicial process, in which cases can take years to be heard in court. The period of waiting for a trial itself becomes a punishment, even if the accusations are eventually dismissed, as they were in Ferreira’s case. “Arrests made by the state are assumed to be in good faith,” said political activist Vernon Gonsalves. “So even when a person is innocent, the investigating authority is rarely questioned or doubted at the time of registering a case.”

Arun Ferreira is now back in jail, once again under trumped up charges.